I enjoy reading interviews with other poets and frequent websites on the craft of poetry. What is interesting to me is that inevitably someone will ask the question of what even constitutes poetry and what makes poets write it. While I am sure novelists and short story writers are asked this question from time to time, poets are asked this question much more frequently. These interviews, articles on poetry, and numerous books that have entire sections devoted to this aspect tells me how many times this question must have been asked before, with many answers in the past, yet the inquiry to get at the bottom of it all has not been diminished. Nor would it prevent the inquirer to ask and the poet to answer this question in the future. And I must admit, it is a question and answer I look forward to reading or listening to as well!

As many of you know, I am participating in Michelle Rafter’s blogathon (read my post on the 12 Reasons I Signed Up For the Wordcount Blogathon). I had originally planned on writing my #blog2013 on my favorite poems and introducing poets one at a time. It sounded like a strategic approach. And I started aptly with the poet, Amrita Pritam, who is my all time favorite. But after I wrote that post, I kept thinking about a conversation I had a few years ago with Punjabi writer and recipeint of the Sahit Akademi award, Gurbachan Bhullar, and it dealt with this age old question: what is poetry and what makes people write it? But more to the point, why do I write it? So I have decided to digress a little from my original plan and am going to add my two cents here:

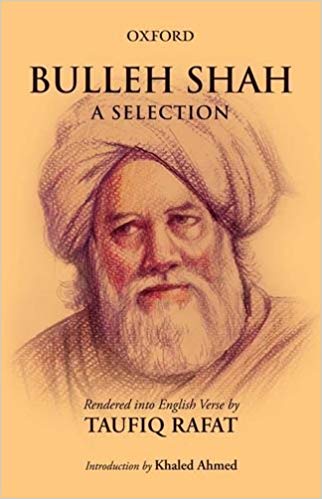

The other day, I was at the local bookstore and bought a book with an amusing title: “Poetry for Dummies.” Although it is not that I identify myself with dummies in the literal sense but being a poet and singer, who is always eager to learn and share my art with whoever is interested. Although poetry usually has a greater degree of attentiveness, concentration, experiment and form than one finds in most other uses of language, still the general perception seems to be that short stories and novels are works of real art because it takes a lot longer in seeding, nurturing and grooming the characters to breath lives into them, and it seems that poetry is easier. Not counting epic poems like Homer’s Iliad or Waris Shah’s, Heer, poems are often thought of at first glance as a one night stand, compared to the novel or short story which are thought of as affairs, with wooing, and building of tension, plot development, etc. To that kind of perception write a few lines that rhyme or don’t, press enter a few times to arrange them some way on a piece of paper, and the poem is born. Easy!

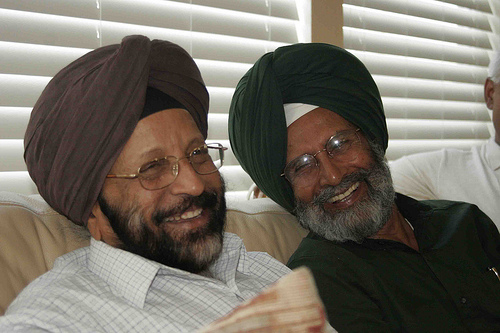

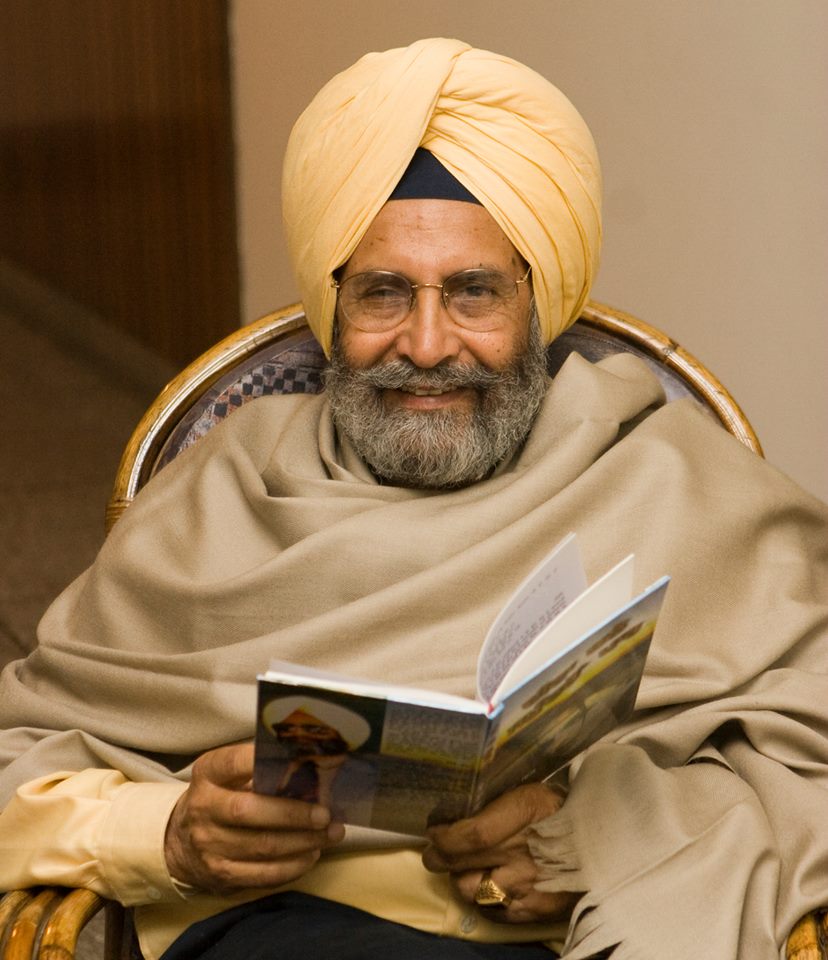

A couple years back when Gurbachan Singh Bhullar visited California, I had the opportunity to attend a few Sahitik Meets and Kahani/Kavi Darbars with him that were organized in his honor by Punjabi American writers living in the Central Valley and the Bay Area California. Most people know him as a serious thinker, speaker, journalist and a distinguished Punjabi short story writer. Which, of course, he is. But he is also a man full of humor and biting sarcasm.

During the trip, we went to visit a good friend of mine, Jagjit Brar, in Rio Vista, and were listening to him talking about the state of Punjabi literature in general. We were sitting on the sofa and having an enjoyable conversation, but as soon as the topic turned to Punjabi literature, I took a look around and saw I was surrounded. Jagjit is also a short story writer, and in her younger years his wife also wrote short stories. I braced myself for what was coming. Like lions, they did not immediately pounce, and instead circles their prey, in this case – me, the only poet in the room. Having read some of my poems in various magazines and journals, they were familliar with the written form, but asked to hear me sing some of them.

So, I sung them some of my poems, such as Umber di Shehzadiye, a poem about man attempting to colonize the moon after he has destroyed the Earth. In my poem, the point of view is Earth, who is writing a letter to her estranged sister, the Moon, warning her no to trust this man coming to her doorstep. Below is an audio image slideshow of me singing this poem in Punjabi, with English subtitles.

After I sung a few more poems at their request, interspersed with light banter, they both cooked a plan to tease me. So here it was three story writers against one poet, including Jagjit’s wife! When I finished, Gurbachan turned to me and gave me a backhanded compliment that to the uninitiated to Gurbachan Bhullar’s writing style will initially think is a real compliment!

“Pashaura Singh Ji,,” he began. And I knew something fishy was going on with the inclusion of the “Ji.” He then shifted his position and said in Punjabi, “We could listen to your poems all day. You have a nice voice.” With caution, I thanked him for the compliment. He continued with the buttering up. “I have no doubt that we are the only two people at the top of this artform, you as a Punjabi poet and me as a Punjabi short story writer.” He paused and gave nothing away in his facial expression.

Then he ended with, “Come to think of it, writing a poem is nothing when compared to writing a short story or a novel. The reasons are obvious. Write a few lines. Doesn’t matter if they rhyme or not. Line them up on a piece of paper and call it a poem. So, really, when you think about it, there is only one great writer sitting here.”

Still, he gave nothing away in his face and both he and Jagjit sat with stone faced expressions. It was a diabolical compliment that switches so quickly at the end that it leaves the person for whom the compliment is intended scratching his/her head.

I looked at him, also seriously, and said, “Bha Ji thank you very much for drumming me and my fellow poets down to the ground especially a minute ago when you were saying I was great with my poems and with my singing. I’ve spent the morning entertaining you two. Now you sing me one of your short stories. Then we’ll see which is easier!”

I looked at him, also seriously, and said, “Bha Ji thank you very much for drumming me and my fellow poets down to the ground especially a minute ago when you were saying I was great with my poems and with my singing. I’ve spent the morning entertaining you two. Now you sing me one of your short stories. Then we’ll see which is easier!”

And all three of us couldn’t help but let out a loud laugh as though we were school children, as our own children, who were on driving duty sat across the room perplexed at how the somber mood my poems usually create had been so drastically altered through this one comment.

Coming back to this book and reminded by Bhullar’s joke, the title prompted me as a poet to align with Dummies assuming this must be about drumming down on reading and writing poetry. But it turned out to be a very informative and useful book with valuable suggestions for people like me and others who are in the same boat and are eager to learn and share. The book opens with a dedication:

“To our families and to everyone – from Enheduanna to the pair of eyes on these very words – who loves reading and writing poetry. Let Poetry for Dummies declare our lifelong thanks.”

Enheduanna, the “earliest author and poet in the world that history knows by name,” according to a google search I did. According to this book she was a powerful, astonishing poet whose poetry was sung bearing a close connection with music, an imprint it still bears today. Since the art of singing is considered as the twin sister of the art of poetry according to this book, I think that the art of poetry is even older than that going as far back as when the human race evolved and first learned to cry when sad and sing when happy. Just as we are innate storytellers, so are we innate poets.

Much interesting and informative this book is as it is, and teaches some valuable hints on how people can learn to read and write poetry, it does not say much about what makes people write it. That brings me back to the same question I started this blog post with, and has probably been asked for the past 5000 years since Enheduanna. Below is a video to a live BBC interview from the 1970s (with English subtitles) with another one of my favorite Punjabi poets, Shiv Kumar Batalvi, another Sahitya Akademi award winner gives a glimpse of the mindset that created all the work we have come to love.

He is asked the question of how he became a poet and he gives one of the most honest answers I have heard. He talks about his upbringing and the class system in India he grew up with, but in the midst of his answer he states simply, “mujhe nahi pata ki mai shaer kaise hogia hun.” (I don’t know how I became a poet.). The interviewer still tries to get to the bottom of it and asks whether it could be that he had some trauma and pain in his childhood, unrequited love, etc. And his answers point to the same thing: sometimes, there is no reason. It simple is. And that is probably the best answer anyone can give on why we write poetry!

Leave a Reply